People sometimes think nothing happens in a small town. Don’t believe them. They clearly haven’t perused small-town newspapers. Presidio County has two papers, which are published every Thursday: the Big Bend Sentinel, out of Marfa, and Presidio’s International. Robert Halpern worked at the Sentinel for thirty years, and he and his wife, Rosario, owned it and the International, which publishes stories in Spanish and English, for about a quarter century. That is, until this past July. The papers have been sold; the Halperns, who are in their sixties, have retired. Long live the Big Bend Sentinel. Viva El Internacional.

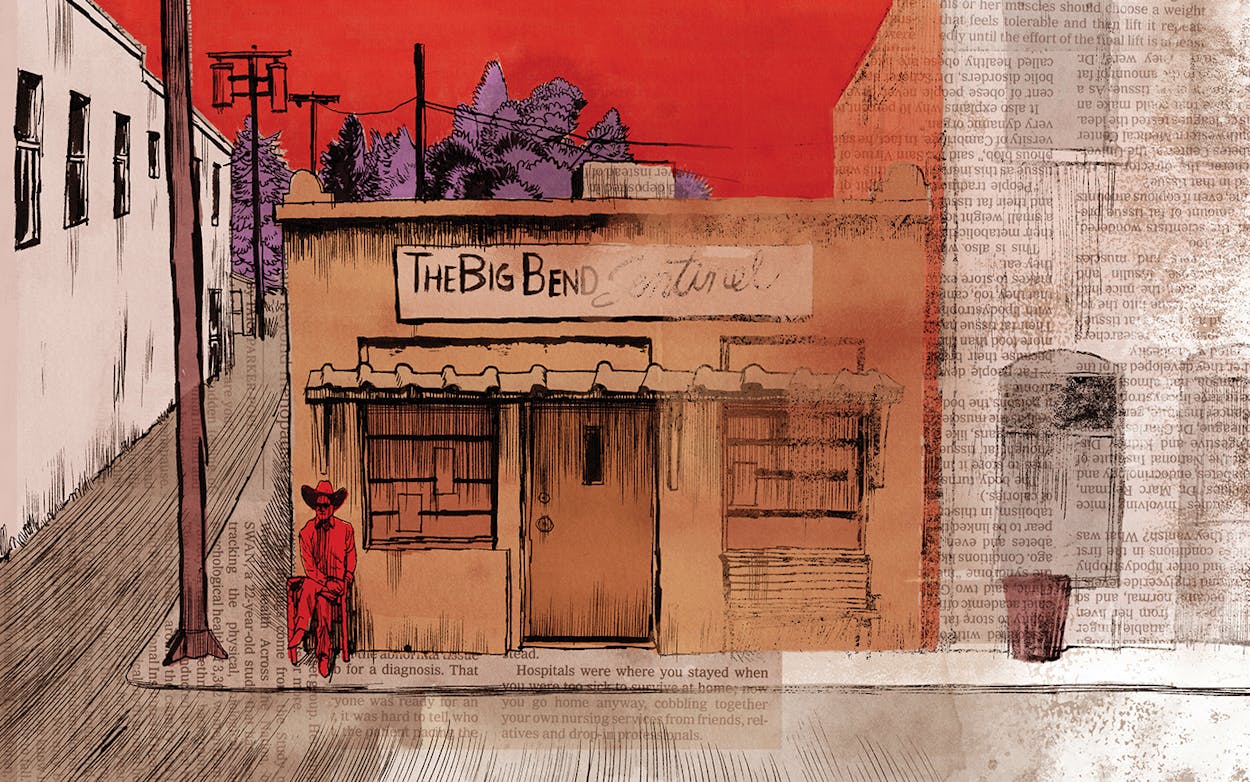

Both papers were produced out of a building on Marfa’s main drag, Highland Avenue. A small front office opened to a large, many-windowed space with the Halperns’ desks on one side, the reporters along the other, and big, sloped tables at the center, where newspaper layout occurred in the precomputer cut-and-paste days. Robert’s a native of Alpine, where his family owned a department store. Rosario grew up in Presidio, one of ten children. They met at an Alpine drugstore, where Rosario worked during college. “It really was love at first sight,” she said.

Robert studied journalism at the University of Texas at El Paso. “I’d always drifted to words,” he said. “I had this great journalism teacher, and my first assignment was to interview Governor Clements. That was it. I was hooked.”

After they married, Robert took a job covering the police beat for the Odessa American, while Rosario finished an accounting degree. The couple next moved back to El Paso, where Robert was hired as an assistant city editor with the El Paso Times and Rosario climbed to vice president of a local credit union. During that time, their daughter, Miriam, was born, then their son Alberto; their third child, Abraham Diego, came a few years later. But the Times eventually changed hands. “It wasn’t a writer’s paper anymore,” Robert said. “And then our friend called and asked me to come help run the Marfa paper.”

The decision to return to the Big Bend, in 1988, was a leap of faith, said Rosario. “We had insurance and good salaries, and we gave it up to go to Marfa. But our families were here. I knew they wouldn’t let us starve.”

Marfa, it should be noted, was not hip or on anyone’s must-see list at that point. This was a poor place. Jobs were scarce; buildings were shuttered. Still, six years after they returned, the couple purchased the Sentinel, in 1994. A year later they bought the International. They remember standing in the doorway, looking at Marfa’s lackluster downtown. “There were parking spaces galore,” Robert said dryly. “Everything on Highland had closed,” said Rosario. “There was no growth, and nothing brought people here. I asked Robert, ‘What did we get ourselves into?’ ”

And yet, every week, there were enough words to fill a paper and enough ads to pay the bills. At a time when many U.S. newspapers are in decline or have folded outright, the Sentinel and International held steady, likely because of the Halperns’ close understanding of their audience. “We’re the mirror of our town,” said Robert, “documenting life and informing the people of this community.”

No week was like any other. There were regular city, county, and school district meetings to cover, and state and national news had to be watched for issues with a local impact. Ranching and agricultural stories always had a place at the paper, and over time, art and culture stories grew important too. Features on new businesses or kids who did something cool were a good bet. So were crime stories and elections. Don’t forget high school sports or the front-page brief on the library’s open house.

The Halperns showed tremendous trust in their writers, who often had no previous experience. I was their first reporter, offered the job after I’d written a letter to the editor in which I outed the mayor as the authorial voice behind the salty weekly columnist “Wahdley Red.” Another writer, still fresh out of college, arrived in a green Toyota and asked for work. That was Jake Silverstein, who eventually edited Texas Monthly and now helms the New York Times Magazine. Dan Keane, who went on to write for the Associated Press in Latin America, was recruited from his server’s job at the old Carmen’s Café. There were lots of us over the years. “We just figured you all could do it,” Rosario shrugged. “It worked out.”

I stayed at the Sentinel for about fifteen years, half of the Halperns’ tenure. It was, I recognized later, where I grew up and where I realized what kindness and commitment really meant. The mantle of responsibility is heavy at a paper in a small town where, unlike in big cities, you live in close quarters with the people you write about. You can’t get anything wrong in print. Misspelled names, misunderstood city council motions, botched quotes, and lopsided points of view are all verboten. Mess up the public’s trust in your words, and you’ve lost a precious commodity. Your friends and neighbors are in these pages.

In far-flung and sparsely populated places like Marfa and Presidio, where for many decades scant reportage was done from outside the area, local newspapers were the chief source of news. This was a burden as well; the Sentinel was a genuine sentinel for the region. “We take our responsibility as the fourth estate seriously,” Rosario said. “If newspapers don’t exist, where do you go for facts? A democracy needs a free press.” Robert regularly filed open-records requests and challenged public officials. If something struck him as suspicious or hinkyness ran high, the Sentinel and International tracked those stories, sometimes for months. No issue was too big for these little papers. A sniper atop a Mexican canyon wall, preying on river rafters. A corrupt sheriff. A terrible fire. A scheme by oilmen to sell water from beneath public lands. A looming nuclear dump. Burros killed at a state park. Immigration and the wall.

In 2001 Rosario stepped out of her financial officer role to dog the story of a Presidio man wrongly arrested in Mexico for the murder of a reporter in Ojinaga, Chihuahua. Her stories shone light onto a shadowy and unjust situation that Mexican officials, after a time, could no longer ignore. He was freed, I’m certain, in part because of her unrelenting coverage.

Contrary to some people’s opinions, the newspaper never held conversations about what angle or news might sell papers and, instead, simply printed stories curated from that week’s happenings. The Halperns demonstrated true creative and editorial generosity. Did a feisty meeting about an arcane planning and zoning issue warrant 1,200 words? Sure. How about a two-part feature on the death of an area vagabond? Yes. The paper’s ace cartoonist, Gary Oliver, seized on any local, state, or national issue he chose, no matter how it might provoke readers. Letters to the editor occasionally spilled onto a second page. A special section of locally drawn comics? Why not? Six action verbs in a single above-the-fold headline? Of course. (“Man assaults woman, rams police vehicle, flees, hits train, fights paramedics, jumps from courthouse.”) The actor Randy Quaid and his wife, Evi, moved to downtown Marfa, trailing California legal trouble, and it wasn’t long before they were publicly at odds with their realtor, their neighbor, the city of Marfa, and a sheriff’s deputy they so despised that Evi blasted him in signs pasted broadside on a cargo truck perpetually parked on Highland Avenue. The paper went faux-tabloid and devoted the entire front page to the spectacle of their eventual arrest. “Evi Quaid tells all, mostly!” “Story goes viral!”

First edition

Presidio County originally included what are now Brewster and Jeff Davis counties. The first newspaper to serve that vast territory was the Apache Rocket, established in 1882 and printed in Fort Davis.

Short, peculiarly local stories about almost nothing were common. The return of turkey vultures in spring was noted annually, for instance, and I once wrote a feature on a woman simply because she turned 94. (“She’s depressed,” Rosario said. “Just write something to cheer her up.”) A rancher pulling down the area’s last working wooden windmill was worth writing about; so were bees whose swarm formed a beard on the courthouse statue of Lady Justice. Rainfall is always news in the desert, and thus we filed many stories about rain, little color pieces that allowed us to relive the deliciousness of storms.

We also followed subtle writing rules that went almost unnoticed. Robert insisted we use the term “undocumented migrant” instead of “illegal alien.” When writing about the people of a community, we called them residents instead of citizens, because Robert said we never knew who had citizenship or not and everyone deserved dignity. Such small things matter, and the paper noticed the small things. The Halperns allowed us, encouraged us, to notice.

Circulation for each paper was the same for years: about three thousand per week for the Sentinel and about one thousand for the International. Although Presidio is the larger town, the International was usually six or eight pages, half the size of the Sentinel, in part because the bulk of the staff was in Marfa, sixty miles away, and partly because Ojinaga radio and papers also appealed to the Presidio audience. And while the Halperns maintained a Facebook presence for their business, as well as a website behind a paywall, their real focus was on the newspaper that readers held in their hands.

The rhythm of the production week was well set. Robert farmed out a few story ideas on Monday. Some of these were specific to Marfa or Presidio, and some, like stories on impending school legislation or a county commissioners’ meeting, worked for both papers. Phones rang, people came by, emails flew. Additional story ideas developed and percolated on Tuesday. Presidio stringers sent stories and photos for the International. Robert earmarked four or five stories each week, chosen for their particular relevance to Presidio, which were emailed to the Halperns’ daughter, Miriam, who translated them into Spanish for the International from her home in Spain. Wednesday passed almost in silence as staffers finished pieces, edited copy, built last-minute ads, and laid out pages. The pages were finished by dinner Wednesday, and Rosario’s brother Junior and his wife, Jessú, drove to the Monahans printing press to pick up the bundled papers, dropping some at post offices and convenience stores along the way home. Early Thursday, loose advertisements were inserted into the papers, subscriber copies were labeled for the mail, and the International was sent to Presidio. By ten o’clock Thursday morning, the week’s work was mostly done. It was a collaborative heave-ho by a small team, the words set pleasingly with an eye toward good design, the pages full of interesting, sometimes vital, sometimes mundane, sometimes quite beautiful stories every single week. You got a lot for a dollar.

The newspaper office was a magnet for lost lambs who regularly deposited themselves among us for companionship and because they liked the busyness of the place.

In my time, the newspaper office was a magnet for lost lambs who regularly deposited themselves among us for companionship and because they liked the busyness of the place. Salvador Peña was a wheelchair-bound, snaggle-toothed double amputee nicknamed El Chupacabra who used to roll onto the highway near his house in Valentine and hitch rides to the Sentinel office whenever he got bored or lonely. He’d beller and josh all afternoon while balancing a tallboy between his knees. He shamelessly smoked in the office and once caught the microwave on fire trying to light a cigarette. It didn’t matter if you had a state official on the phone or a schoolkid present for an interview, he wouldn’t tame down or quiet. We adored him.

Pepper Brown was a dashing septuagenarian who was enchanted with Teresa Juarez, Rosario’s sister, who oversaw the front office and is lovely in manner and appearance. Pepper gazed at Tere while she answered the phone or typeset birth announcements. A former cowboy, Pepper sometimes drew while in the office, and his ballpoint pen rendition of a bronc stomper atop a bucking horse hung in the Sentinel. One afternoon, Pepper abruptly left his post, crossed the street to the dime store, and then disappeared into the newspaper bathroom upon his return. After a while, he reemerged, arranged himself on a bench, and waggled an eyebrow at Tere. He’d apparently bought brown shoe polish and applied it to his silver hair, eyebrows, mustache, and beard, to arresting effect. “It was impossible to stay mad at them,” Robert said of the regulars. “The paper had an open door to ideas and life. They wanted someone to listen, and we listened.”

Other folks relied on the office to fulfill immediate, local needs. New to town and want to find a Passover celebration? Go to the paper, they’ll know someone. Is Walmart really coming? Stop by the paper, they’ll find out. Need to vent about the school or politics? Rant for a bit over at the paper, they don’t mind.

I have never worked for a big-city paper, and I don’t know if these things happen at city desks there. I suspect they do not. Corporate outfits are unlikely to have such reliably direct and open access to their audience. Small-town readers are passionate and smart and quick to convey praise or criticism accordingly when they see you at the post office, the gas station, or the track meet. While I was reporting a series of stories about a high-stakes water issue, a rancher I hardly knew grasped my arm near the canned corn at the grocery store. “You keep being brave, girl,” he said. “Keep them bastards on the run.” What is important is right in front of you. Lessons in humility, tact, and craft abound.

The papers’ new owners will learn that firsthand. Maisie Crow is an award-winning documentarian, and her husband, Max Kabat, owns a marketing consultancy. They’ve lived in Marfa since 2016 and started talks to buy the papers last year. They’ve moved the newspaper office to a freshly renovated property they own, a couple blocks off Highland. “Max and I hope to be good stewards of the Big Bend Sentinel,” Crow said, “and to build upon the legacy that the Halperns and their predecessors created.”

Tucked in the center of the Sentinel’s old masthead is a little drawing of a cowboy beside his horse, their backs to the reader, looking off toward the desert mountains. Some folks think the cowboy is admiring the view; our friend Boyd joked that he was just taking a leak. Lately I’ve thought there’s a different answer. Maybe he’s looking at the future. “I want to see the papers continue for one hundred years,” said Robert, “though it’s time for us to let it go. All we wanted to do was tell the story of this area and these people. I think we did that.”

This article originally appeared in the October 2019 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Very Local News.” Subscribe today.